21(38)

using more than zero days is 3.7 times higher in the treatment group

compared with the control group and there is a statistically significant

higher risk in the treatment group of using up to more than 30 days, but

not more than five weeks of parental leave. The effect is to a large extent

dependent on a shift from not using any or only a few days of parental

leave before the reform to using approximately 30 parental leave days, that

is, the reserved month.

The results for the second reserved month are presented in the second

column of Table 3. The estimates show that the treatment group has higher

risk of any use up to more than 60 days, but not more than nine weeks of

parental leave days, thus, the two reserved months. Similarly to after the

introduction of the first reserved month there is a clear shift, but instead of

using approximately 30 days, the fathers use more than 30 days and up to

about 60 days of parental leave.

Turning to the potential effect of the gender equality bonus we do not find

any shift of the same magnitude and there is no statistically significant

higher risk of more usage at any point in time when we compare the

treatment group with the control group.

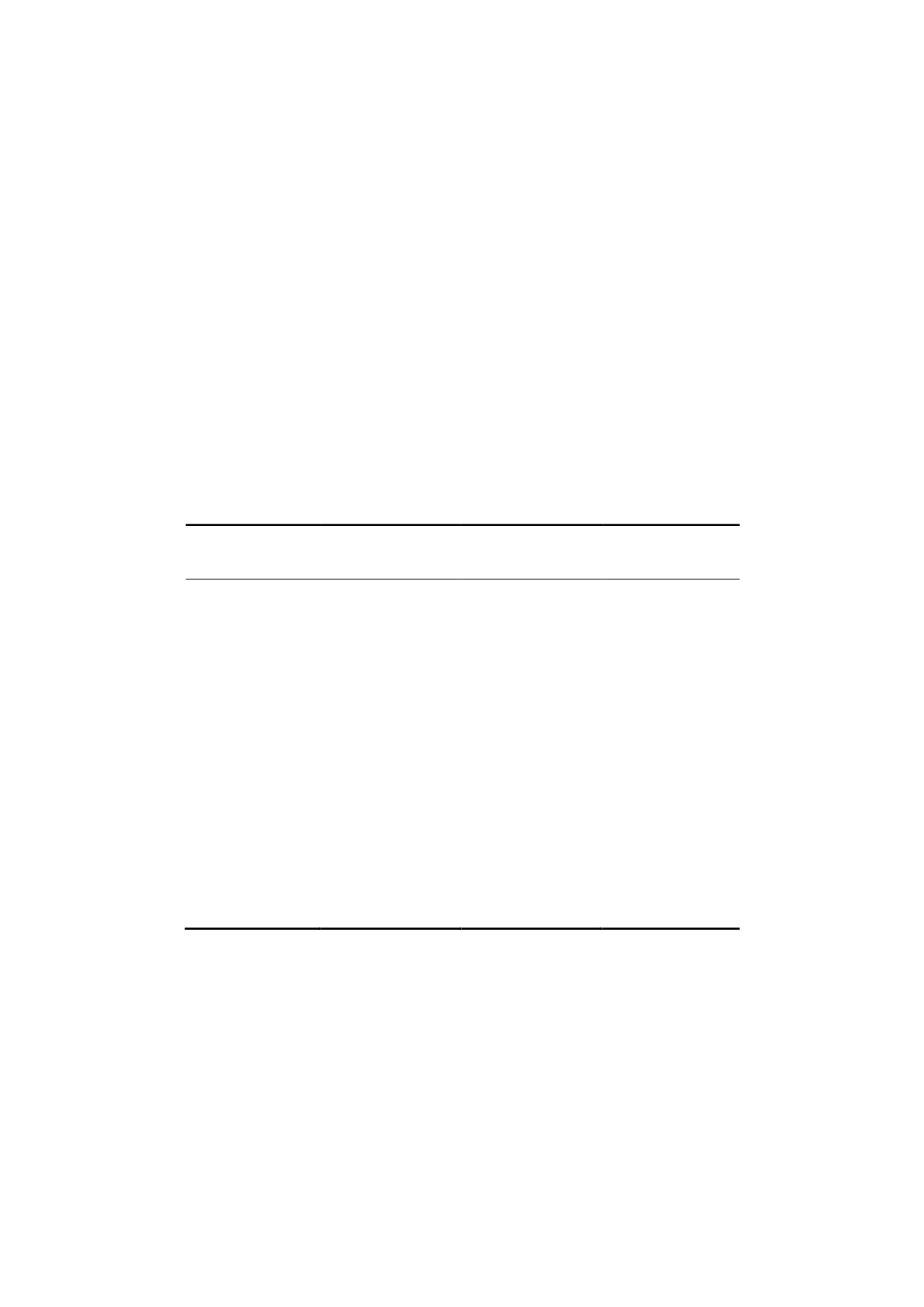

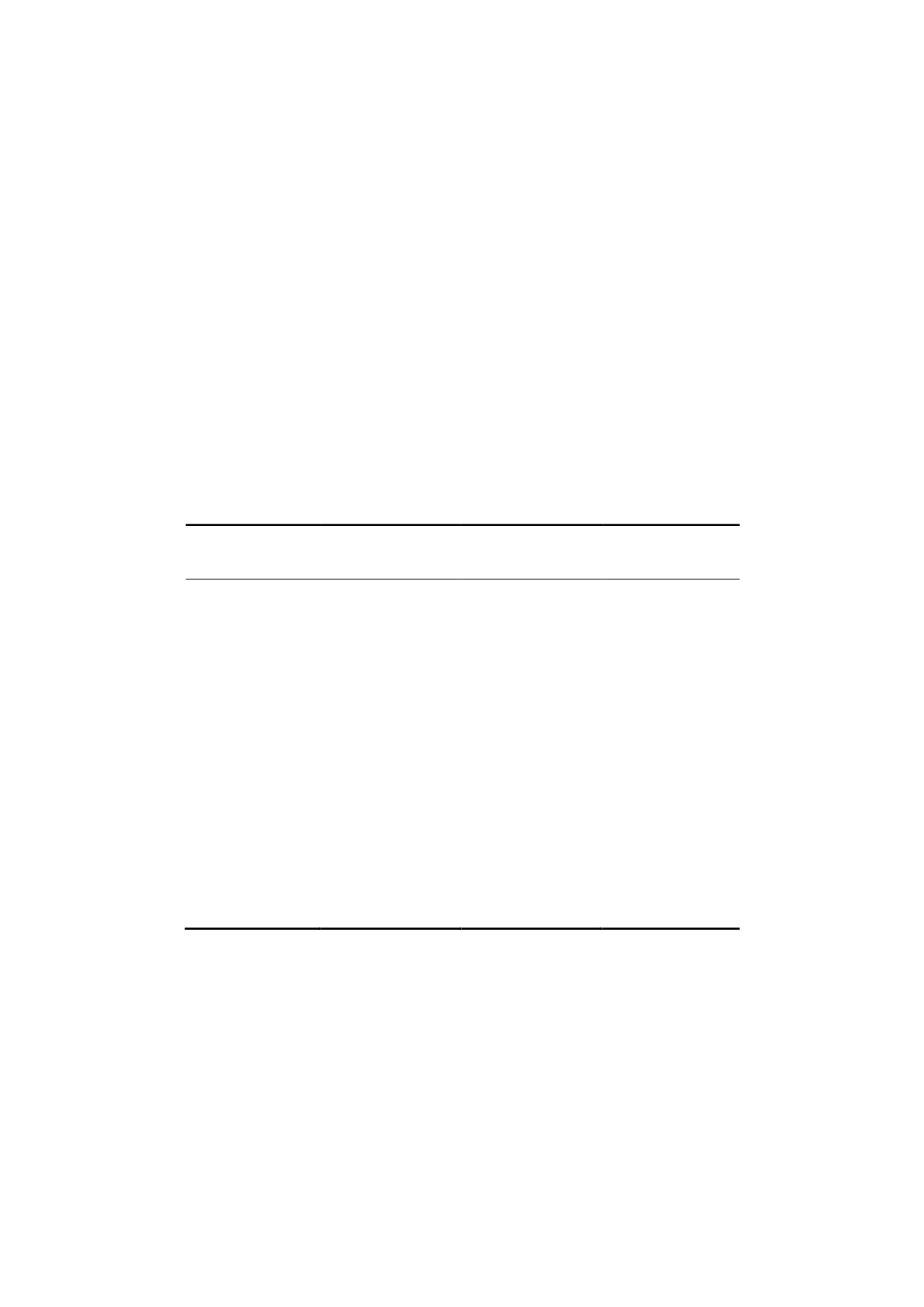

Table 3

Risk of least number of earnings-related parental leave days, odds

ratios. Estimate of being in the treatment group compared with control group.

First reserved

month

Second reserved

month

Gender equality

bonus

>0 days

3.71***

1.23**

1.06

>1 week

3.69***

1.27***

1.06

>2 weeks

3.45***

1.32***

1.05

>3 weeks

3.13***

1.42***

1.01

>4 weeks

2.41***

1.48***

1.00

>30 days

1.41***

1.67***

1.00

>5 weeks

1.01

1.64***

1.01

>6 weeks

0.95

1.66***

0.99

>7 weeks

0.96

1.66***

1.00

>8 weeks

0.95

1.54***

1.05

>60 days

0.96

1.23**

1.12

>9 weeks

0.97

1.15

1.11

>10 weeks

0.94

1.03

1.16

>11 weeks

0.94

0.99

1.12

>12 weeks

0.93

0.99

1.10

>13 weeks

0.94

0.96

1.05

*** Significant difference (1 percent level) between control and treatment groups.

** Significant difference (5 percent level) between control and treatment groups.